Jane O’Neill

Bourke Street Leisure Centre

31 January - 28 February 2026

This project is Supported by the City of Melbourne Arts Grants.

The artist wishes to acknowledged Kahli and Aaron Perkins at Fullstop framing and Caz Leadbeater from ThreeByOne.

Exhibitions

That Amniotic Feeling

Jane O'Neill has long been drawn to the shimmering, chlorinated lengths of the swimming pool. She first exhibited pool works in 1997 at Fortitude Gallery in Brisbane. White and navy tiles were plastered up the wall—the instantly recognisable horizontal expanse of a pool floor rendered vertical, a familiar sight tilted up. You could imagine you were walking in water. Then, after a break, in 2014, O'Neill returned to the pool once more. She held a show in Naarm/Melbourne at the Living Museum of the West, where she invoked the pool's neat lane lines again, this time drawn in dry chalk on a concrete floor. She began identifying publicly, via her Instagram account handle, with the medium lane. (Not too fast, not too slow; not overly competitive, but not unserious either.) More pool work followed.

Increasingly, O'Neill found she was using a new material: denim. The thick cotton most often comes dyed in shades of indigo. Denim is also a fabric with an especially watery production process; the creation of a single pair of jeans requires between 3000 and 4000 litres of water. It is a material which invokes the blue of pool water in multiple ways. At first, O'Neill recycled op-shop denim. Then her works started growing in scale. Now, she uses scraps of wastage denim sourced from a company in Fitzroy.

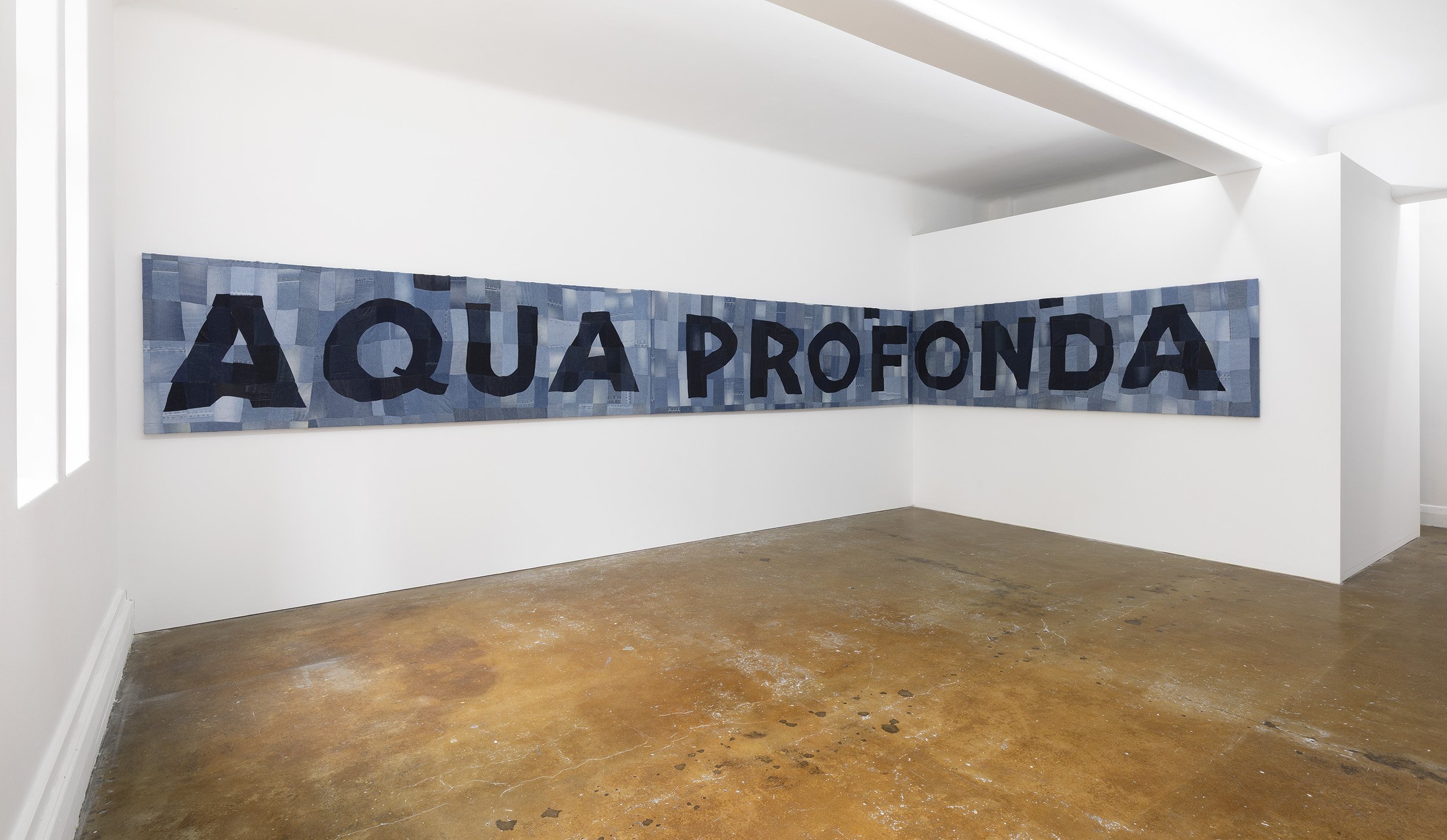

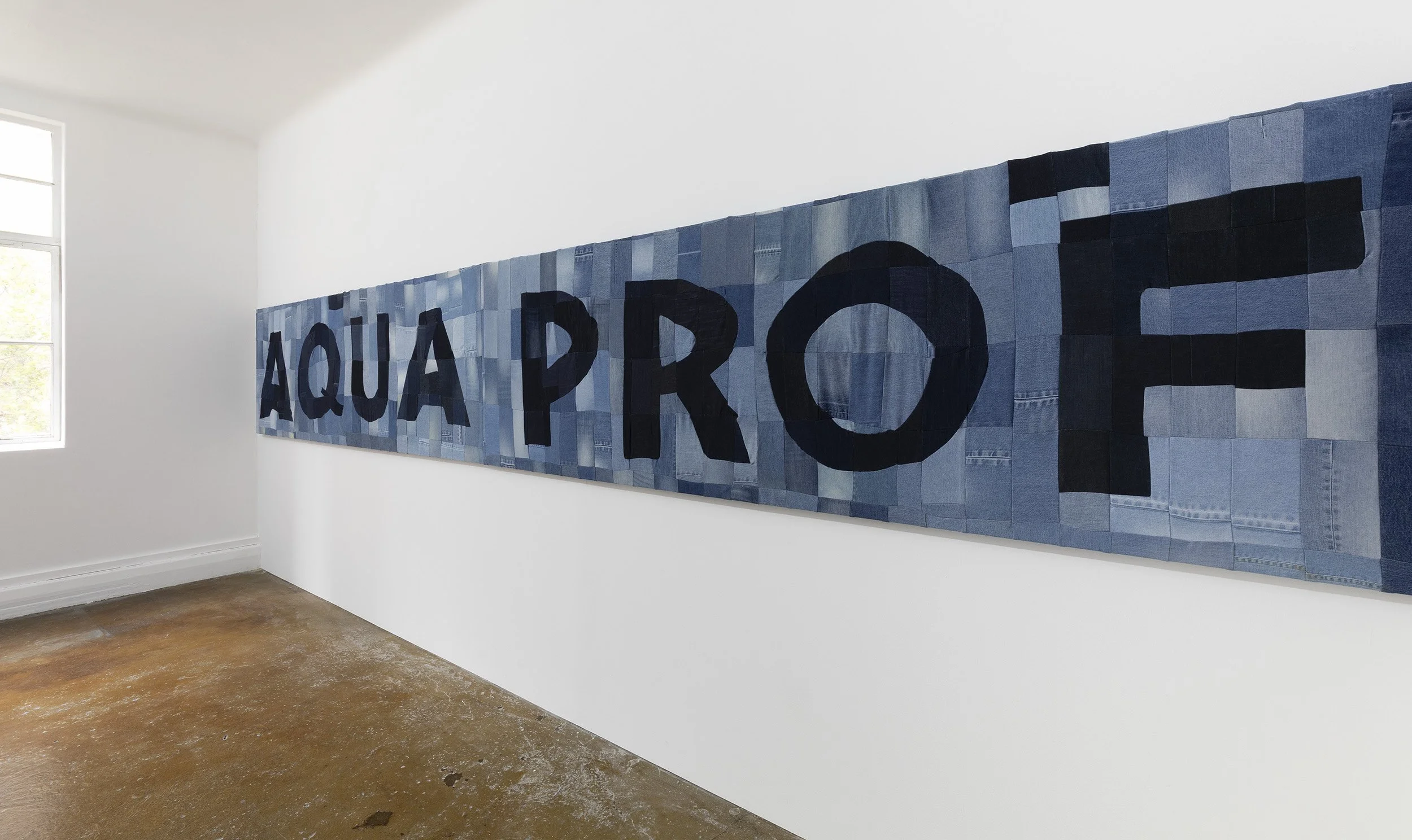

For Bourke Street Leisure Centre at Void_, she cut pieces of denim into 20x10cm rectangles, dimensions similar to those of a typical public pool tile, and sewed them together to create metres-high, quilt-like forms. (O'Neill feels an affinity towards the quilts made by the women of Gee's Bend, Alabama, who use similar construction techniques.) The resulting works resemble a view of an empty pool from above, with navy T-shapes marking out the lanes. Like the 1997 tile works, the denim pool floor's horizontal orientation is tilted up on its axis, defamiliarised.

The rectangular components of O'Neill's compositions bring to mind the classic modernist grid. Yet the overall effect is wobbly and off-kilter. The panels are sutured together neatly but imperfectly. This speaks to what O'Neill identifies as a local tradition of "wonky abstraction" (think Nixon, Nolan, Newman, etc.), an Australian tendency that is a gentler counterpart to the international legacies of hard edge painting and other similarly severe modes of abstract art.

The pool appeals as a subject for the formal challenge it presents—representing the rigid, geometric structure of the tiling as well as the undulating shards of light passing through filtered water. It also has multitudinous symbolic potency. For David Hockney, to pick an iconic piscine painter, the pool is sensuousness, California sun on tanned male torsos, American money, not-England. The technical challenge of painting a splash. Hockney's pools are usually private. The photographer Wolfgang Tillman, by contrast, saw the beauty in the public bath, the German Hallenbad, with its grubby Mondrian-esque tiles, safety railings, visible drainage systems, and sterilised ripples. In a place like Melbourne, where the body is concealed for most of the year, the few months where the public pools are packed are filled with lazily desirous stares. (There is a David Foster Wallace story, "Forever Overhead," which unforgettably likens the smell of semen to that of the pool: "a bleached sweet salt, a flower with chemical petals.")

The phrase "AQUA PROFONDA" indexes one specific public pool. It's the famous sign at the end of the Fitzroy baths—"deep water" in misspelled Italian, painted up in the '50s by some hapless Anglo trying to stop the migrant kids from drowning. The phrase also appears in Bourke Street Leisure Centre, signalling the show's alignment with the public pool and all its democratic chaos.

What else does the pool mean to O'Neill? There is the return of the repressed Catholic in the trinity of upright lane lines/crosses. Agnus dei, aqua profonda, amen. To broach the cool chlorinated surface of the pool is to enter holy water, to self-baptise before swimming laps? It would also be possible to try to explain the work via the prism of a Theory—hydrofeminism, for example—but ultimately, O'Neill sees the deepest draw of the pool in primal terms.

"The honest truth," she told me recently in a conversation at her studio, "is that I think when you're in water, you are the closest that it's possible to be as in the fetal state." Some people seek a return to this state via drugs or drinking or sex. Others plunge beneath water at the beach or the bath or the swimming pool. (Many partake in more than one of these activities.) All of us are trying to return, in some way or another, to that amniotic feeling—to feel our limbs turn weightless in liquid, to feel our eyes and nostrils encased by fluid, to be nourished once again by the mother's body. The pool: maybe it's not that profonda, but maybe it is.

Cameron Hurst

Jane O’Neill | Seam by Seam I, II, III 2024 - 2025 | polyester and cotton on denim, hoop pine stretchers | each panel 2200 x 3150 mm | Photo Christian Capurro

ENQUIRE

Jane O’Neill | Deep water 2025 | polyester and cotton on denim, hoop pine stretcher | 920 x 8850mm | Photo Christian Capurro

ENQUIRE

Jane O’Neill | Bourke Street Leisure Centre | Photo Christian Capurro

Jane O’Neill | Deep water 2025 | polyester and cotton on denim, hoop pine stretcher | 950 x 8850 mm | Photo Christian Capurro

ENQUIRE

Jane O’Neill | Deep water 2025 | polyester and cotton on denim, hoop pine stretcher | 920 x 8850 mm | Photo Christian Capurro

ENQUIRE

Jane O’Neill | Bourke Street Leisure Centre | Installation view | Photo Christian Capurro